Australia is home to some of the most unique and extraordinary wildlife species on earth. But a silent killer is threatening their existence: rat poisons known as Second-Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides. These potent poisons, commonly known as ‘SGARs’, are wreaking havoc on native species, from iconic eagles to curious quolls.

In a remarkable act of leadership, Albury City Council has removed these toxic chemicals from all council-managed facilities — setting a powerful example of how we can protect Australia’s biodiversity while fostering coexistence with the wild world.

Following a national audit of all local governments in Australia by Animal Liberation, which revealed the use of SGARs at 12 major sites — including the Albury Botanical Gardens and Albury Airport — In January 2025, Albury City Council took this groundbreaking step to protect native wildlife. The council decided to eliminate these poisons entirely from its management programs. This action has directly protected over 350 bird species and countless mammals who call the region home.

Albury’s decision is not just a local triumph, it’s a call to action for councils across New South Wales and beyond. By removing SGARs, Albury has drastically reduced the risk of secondary poisoning for predatory and scavenging species who play vital roles in maintaining ecological balance. This initiative demonstrates that respecting wildlife and coexisting with nature is not only possible, but essential for preserving Australia’s rich biodiversity.

Rat poisons like SGARs are insidious killers. They work by preventing blood from clotting, leading to slow, painful deaths from internal bleeding. While intended for rodents, these poisons do not discriminate—they infiltrate entire ecosystems through food chains. Native predators, like owls and eagles, often consume poisoned prey, leading to secondary poisoning that can devastate local populations.

Recent studies reveal the alarming scale of this problem:

The use of poisons to control wildlife in Australia has a long and troubling history. From the early 19th century, substances like arsenic and strychnine were widely used to kill dingoes and rabbits. These poisons have been followed by the deployment in Australia of 1080, a cruel poison banned in most other countries. These practices have left scars on ecosystems contributing to Australia’s tragic distinction as having one of the highest rates of mammalian extinctions in the world.4

Imagine the haunting silence left behind when owls vanish from an area due to poisoning. These animals are not just victims — they are vital threads in the intricate web of life that sustains us all

Rat poisons like SGARs represent a continuation of this toxic legacy. Despite their well-documented risks, these deadly products remain alarmingly easy to purchase in retail and online stores across the country. Unlike other nations, such as the United States and Canada, which have implemented strict regulations limiting their use, Australia lags behind in protecting its native species from this preventable harm. This lack of oversight leaves countless animals vulnerable to the toxic ripple effects of SGARs.

Albury’s success shows us what is possible when we prioritise coexistence with wildlife over convenience. However, much work remains to be done. Across New South Wales and Australia, SGARs are still widely used in residential areas and council programs. Advocacy groups like Animal Liberation are leading efforts to push for statewide bans on these poisons through petitions and public awareness campaigns

You can be part of this change:

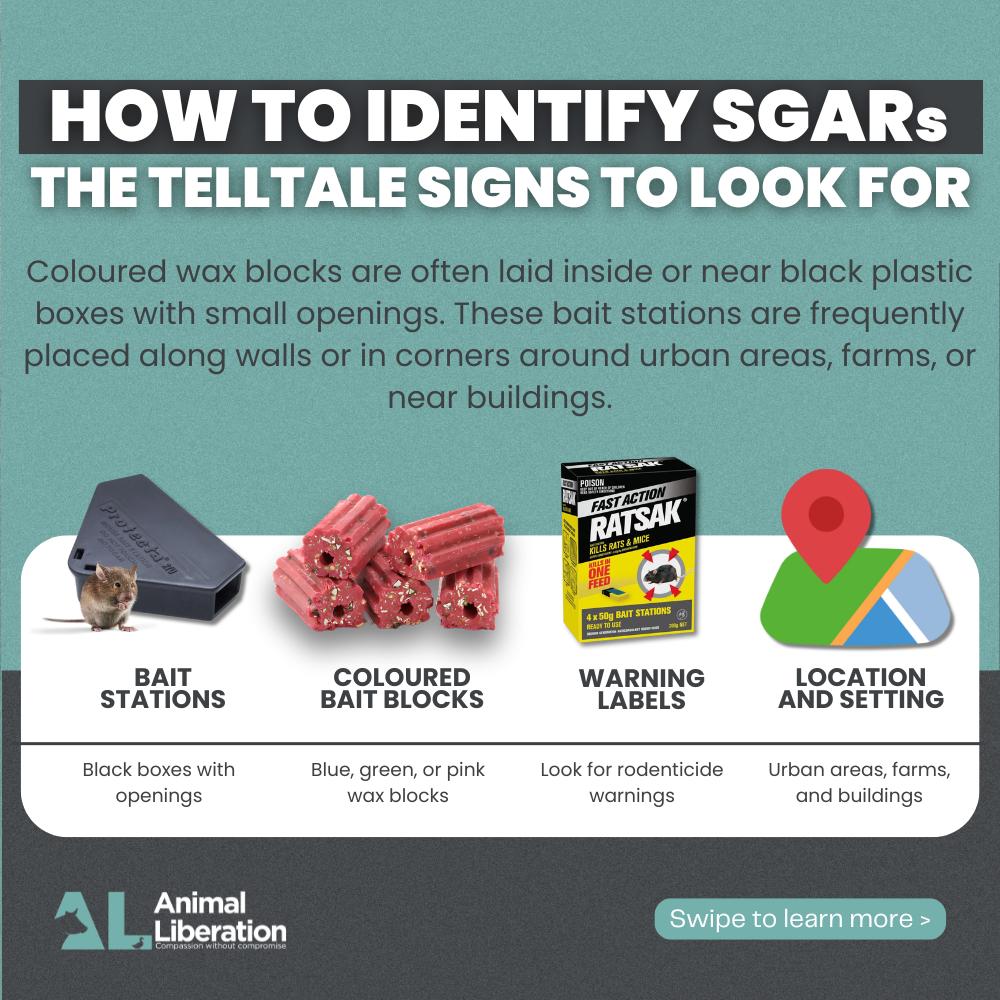

Products containing SGARs are often sold under brand names or generic labels that can make them hard to identify at first glance.

Commonly available SGAR products include:

These products are often brightly packaged and placed alongside everyday household items, making them easy to purchase but devastatingly harmful when used. If you spot these products being sold or suspect they’re being used in your neighborhood, report them immediately so advocacy groups can take action.