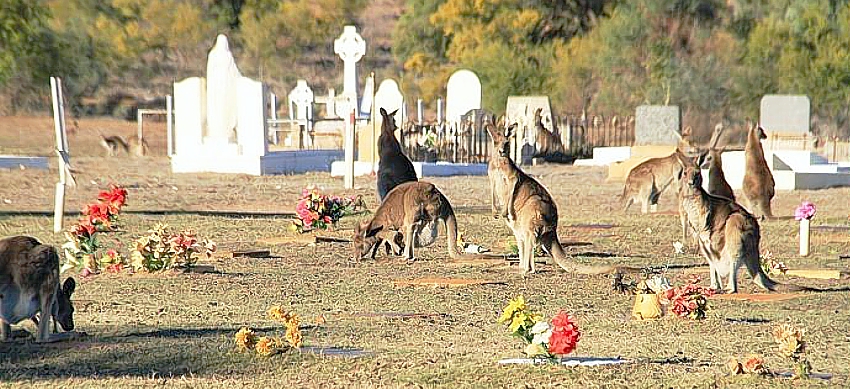

ABOVE: from a hunting website in Queensland a year ago. As in Queensland, the NSW government is actively calling for ‘volunteers’ to shoot the wildlife – “to help the farmers” they say. Apart from basic ethical and usefulness issues, in both states there is no evidence of oversight on capacity to shoot accurately; take care of joeys; or manage any welfare questions.

by Maria Taylor –

Taken from: https://districtbulletin.com.au/us-end-game/

THE FOLLOWING IS an excerpted chapter from book Injustice, the War on Australian Wildlife by Maria Taylor. The subject is Australia’s fraught relationship with much of its wildlife since colonial times and how certain values and beliefs have stuck with many of us in this country. The kangaroo species that are hunted and unjustly treated as pests is the standout case study.

The mainstream version of our relationship to this unique marsupial is told every day as with one voice by graziers and some farmers, major political parties, some applied ecologists, mass media and in most cases, the kangaroo ‘harvesting’ industry. Together they support the world’s biggest terrestrial wildlife slaughter.

The countless millions of kangaroos people believe are bounding across the landscape are in large part a mathematical figment that has received well-deserved deconstruction.

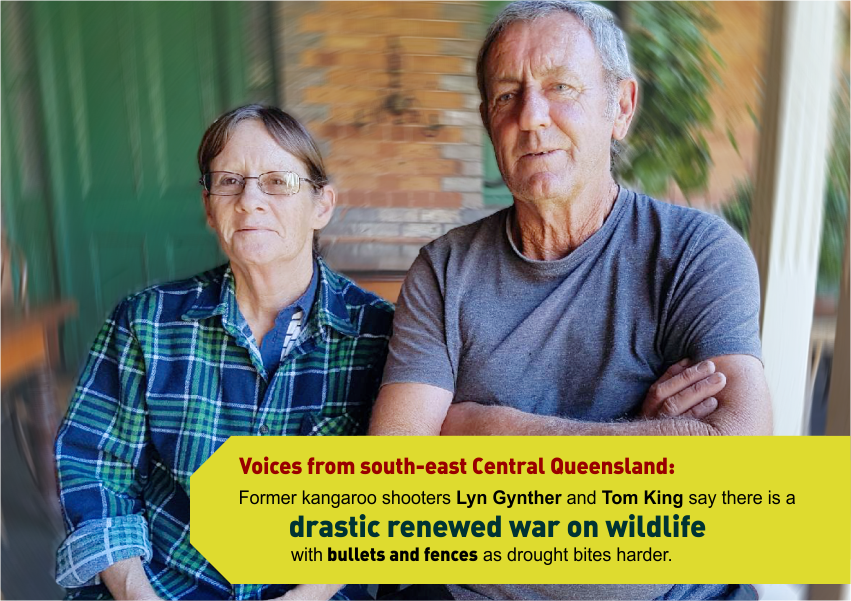

In this chapter Taylor talks to two former ‘roo shooters who tell a different story – not from a desktop, but from ground-level. They reveal the horrors that are going on right now in south west Queensland in the name of drought relief and to prop up hopes for revival of a sheep industry there. And the same ideas and proposed solution to blame kangaroos are seeping into NSW.

— Tom King Snr, Cunnamulla

— Dr Arian Wallach, University of Technology Sydney,

conducting dingo research in Central Queensland

LYN GYNTHER TELLS me that she lives next door to an abattoir. She recounts a recent experience with a load of cattle. They had been left there by the owner over the weekend with no feed and as much water as a dog would drink in a day. She got on the phone to the owner and told him that if he didn’t come around with some feed and water, she’d do it and bill him. He came.

I had gone to Central Queensland to interview Lyn Gynther and Tom King about their first-hand experiences. Lyn, from around Warwick, is a fighter for animals but she was also a killer of animals as a former roo shooter. Tom King from Cunnamulla is also outspoken for wildlife these days while still a licensed and sometimes practicing roo shooter. To be accurate, he’d like to be a roo shooter who can still make some income in an arena the kangaroo industry and state and national governments insist is sustainable wildlife management.

Given his unusual outspokenness he’s also been pushed off properties and called crazy; or lying for breaking the tradition that demands conformity and silence towards outsiders – characteristic of many communities, particularly rural communities, in Australia as elsewhere.

But with an intractable drought pitting domestic stock graziers against the commercial kangaroo ‘harvesting’ business, let alone wildlife welfare advocates, things have been breaking out into the news. From the kangaroo industry’s perspective the wildlife ‘resource’ is being wiped out. Tom in particular has interested local journalists by fingering as a major culprit the kilometres of cluster fencing nominally aimed at stopping wild dogs that maul sheep. But the fences also cut across remaining wildlife corridors to water and to opportunistic forage.

Both Lyn and Tom told me about the destruction being rained down on kangaroos and wallabies and, more quietly, emus, by a state government mitigation program to help the graziers. This entails generous open season permits to shoot macropods for three years being issued for 2017–2020. ‘Mitigation’ has in some places opened the door for recreational shooters being invited onto grazing properties to blast away at any wild-living animal unfortunate enough to be caught up by the fencing maze.

This is happening on Mitchell Grass plains interspersed with mulga and Gidgee native tree belts where there has been conversion since the mid-1990s from sheep to frequently opportunistic cattle grazing – a situation that local and state politicians in 2018 herald as starting to reverse itself thanks to the fencing. They have hailed the move back to sheep as the newest saviour for outback communities like Cunnamulla. Back to tradition is a time-honoured Australian response to a challenging environment.

WHAT SHOULD BE predictable drought, (it’s happened since colonial days), has been intensified and made less predictable by present-day climate change. Six-, seven-year or longer drought now frames a renewed war on wildlife as paddocks lie bare of forage. It reads like a 21st century replay of the colonial annihilation of the native inhabitants from ‘private property’ that new settlers claimed across the landscape.

Talking to the current settlers, long-standing myths, demonization, and false facts soon emerge regarding remaining kangaroo mobs, complicated again by the activities of the commercial harvesters. For example, recent policies to target only male animals (to get around the bad public relations image of the treatment of joeys) destroys stable mob structure and behaviour while increasing the number of kangaroos seen overall as more females survive to maturity.

The situation is further complicated by past property management practices – like opening artesian stock water opportunities that attract wildlife on land that did not naturally support water courses. That said, going back a step further, few current owners know what the colonial settlers did in altering the landscape – as in widespread tree removal, or erosion from overstocking, both drying out previous wetter areas.

What is seldom if ever talked about is sharing the landscape with the original inhabitants:

kangaroo, wallaby, emu, brolga, and co-existing with the natural predators, dingo, eagle. That might lead to thinking outside the box in the direction of other enterprises – like inland tourism.

The sheep industry nowadays actively promotes hundreds of kilometres of exclusion fencing not only in Central Queensland but around Australia against dingoes but also against kangaroo, wallaby and emu “pests” as they call them, and feral animals like wild pigs and goats. There is an admission that the business is either so marginal by location or weather or is so greedy that keeping out kangaroos, wallabies or emus that might share some vegetation over many thousands of hectares, is a make or break situation.

Lyn says she was a wildlife carer, always caring for something, before she started shooting (at the age of 17, now 55) in the early 1980s. She worked along with her ex-husband. “We got ourselves into a situation where there was no work out home; we had nowhere to live; we went to the local council at Barcaldine and enquired about Centrelink payments, denied; they said move back with your parents.” They got a loan from family to set up a truck, the spotlights the guns the racks and went shooting.

As someone who cared for animals how did she cope? “I had to switch off. It desensitises you. Every normal person has to desensitise when you have to do this killing every night.”

(Tom interjects, there was a time in the late 80s when it got to him and he just didn’t want to do it.) Both agree that they had to because it was all that was coming in as income.

Lyn says she was a wildlife carer, always caring for something, before she started shooting (at the age of 17, now 55) in the early 1980s. She worked along with her ex-husband. “We got ourselves into a situation where there was no work out home; we had nowhere to live; we went to the local council at Barcaldine and enquired about Centrelink payments, denied; they said move back with your parents.” They got a loan from family to set up a truck, the spotlights the guns the racks and went shooting.

As someone who cared for animals how did she cope? “I had to switch off. It desensitises you. Every normal person has to desensitise when you have to do this killing every night.” (Tom interjects, there was a time in the late 80s when it got to him and he just didn’t want to do it.) Both agree that they had to because it was all that was coming in as income.

“It’s hard, dirty, filthy work that’s desensitising. Your brain’s dead. When you get home, then you’ve got to salt your skins, unload your roos, do your knives, reload your bullets, then you get a few hours sleep and then you’re up and at it again.”

She did it full-time for three years and then part-time for a total of five years. She had two children in that time. Her ex-husband was in it lot longer. She went and managed a motel and he was still shooting. “We left Barcaldine when the kids were five and seven and he did it until then.”

“We used to also go pigging, not like these people do with dogs, we never had dogs that were allowed to touch pigs… Or we’d take ‘em home and sty them, clean them out. My job was to shoot a roo every second day to feed the pigs.

“If there was a joey on board … grass was high couldn’t always see the pouch; if I hit a doe instead of a buck … I had another joey to rear.

She stopped shooting finally, sick of the heavy work, being tired and exhausted; “My parents were looking after the kids while I was trying to shoot at night, trying to sleep through the day, and mum didn’t want kids all day and all night”. In the end her husband employed an offsider for $50 a night.

“I know now how many macropod families I’ve blown apart

“I struggle now, get quite depressed, since I have educated myself on the biology and the mob structure and that sort of thing. Because I know now how many macropod families I’ve blown apart and completely destroyed and caused chaos within those animals.”

While it is soothing to view ‘game’ or ‘pest’ animals not as families but as mechanical units that managers can count and kill, destroying the group structure, the natural behaviours and interactions has consequences. Quite apart from welfare considerations, people often have no concept of what they are unleashing.

Dingo, wild dog, predation on sheep is the official reason for the Central Queensland cluster fencing across contiguous properties. People will tell you that the years of cattle farming encouraged the dingos to breed up because cattle producers aren’t particularly threatened by wild dogs. Or that graziers, out of desperation at the dingo predation, went out of sheep into cattle.

But dingo researcher Arian Wallach explained how indiscriminate poisoning and killing can makes matters worse for producers as they struggle to maintain domestic animals in an existing ecosystem that has had some stability and predictable patterns of behaviour.

Firstly where dingos are persecuted, there are likely to be more herbivores, among their natural prey. In dryer times that prey is more likely to be the kangaroos that most graziers also don’t like and kill, along with the commercial industry take.

Researchers at the University of NSW again confirmed that where dingos are culled there is more kangaroo activity and conversely there is more grass where dingos are not culled. The whole system is correlated with irregular rainfall events. Thus, current solutions by graziers and governments of fencing out and killing both the predators and the natural prey, is an expensive destruction of an existing ecological pattern with no promise that it has any effect on the real threat, the drought.

Also less well known is that killing the dingos indiscriminately or removing the dominant males creates chaotic family structures.

Wallach said that the surviving young, ‘homeless’ and uneducated dingos, are likely to be the ones preying the most on an easy target – sheep. The same would be true of other wild dogs. It becomes a vicious circle that has also been observed in North America with persecuted wolf populations.

A population-stabilising mob structure applies also to kangaroos. Unmolested, a mob is led by an alpha male, the prime target for shooters. Not only are they big and easily seen, but they stand and face the threat as the mob disperses. Against guns.

Lyn Gynther said that in Queensland grazing lands now, after years of ‘harvesting’ and pest management, people hardly know what a big kangaroo is. “The (male) roos we were shooting back then were massive animals. They used to keep all the young males in line. And all that’s gone now. So you have young stuff raping immature females, causing problems like prolapses, infections… It just goes on.”

Pest management, whether it is by graziers or the city of Canberra, perpetuates the biological imbalance. They call it ‘culling’ which in nature takes out the weak, but here it’s the strongest males that go first.

From their on-ground observations, Lyn and Tom think that the gene pool is changing with kangaroos that are continually hunted producing smaller offspring. (Lyn agrees as carer of orphaned joeys.) Tom says that by 1984 shooters meeting at his place agreed the roos are not as big as the old fellas used to be. That has meant they have to shoot more for the same amount of money for skins and meat.

The roo shooting system has been an agreement between a professional shooter and a number of property owners.

Says Lyn, “We used to take a trailer as well as the back of ute and a normal nights shooting was 60–70 roos, five, six, nights a week in those three properties [where they had a deal to shoot]. A really good nights shooting was 100 plus. The animals were there all the time.”

Massive outback acreages are involved – tens and hundreds of thousands of hectares. While the Red Kangaroo ranges more widely in arid country, Eastern Grey Kangaroos adhere to a home-range system that would account for mobs being there “all the time”. Until the animals weren’t there anymore in any predictable way.

Nowadays says Tom, “One bloke said he reckoned he had 10,000 kangaroos on his country. I went out and shot 10 kangaroos for the night and I wouldn’t have seen 100.”

Lyn agrees. “Nowadays shooters are bringing in 10 or 15 roos a night. If they come in with 50, 60 you suspect they’ve been in the national park.”

Faithful media repetition of local claims that nevertheless kangaroos are on Central Queensland properties (and elsewhere inland) in “plague-proportions” may in fact be a function of perception. As one sheep grazier told me, in the drought the only reasonable patches of grass come up as a result of fleeting rain storms. Then all the kangaroos in the region are likely to descend and be seen as a plague. Research has shown that sheep and kangaroos are only in competition for grass during a drought. (Terence J Dawson, Kangaroos, 2012. CSIRO Publishing, p145.)

The fencing and freelance ‘mitigation’ shooting that has characterised Central Queensland in past years has also disrupted previous animal home-range patterns. When one grazier puts a mitigation licence or fence into effect, it’s likely that the neighbouring property may suddenly see hundreds of fleeing animals not seen previously.

The last Australia-wide count of professional kangaroo shooters and related workers yielded a workforce of 4,000–5,000 maximum. The government frequently claims 4,000 jobs are at stake with the commercial kangaroo industry. However, Lyn and Tom say most shooters are not full-time, just weekender, part-time shooters. Many are leaving the industry because they cannot make even a part-time income for the trouble.

This is despite the fact that the officially published census of kangaroos has grown by remarkable millions (particularly for Queensland over three years despite severe drought and persecution). But Lyn points to the anomaly between the government’s allocated quota and actual take as an indication that the animals are not there.

In Queensland shooters have not taken more than one quarter to one third of the quota even in their best years of the past decade before the loss of the major Russian market in 2012 and again in 2014 (thanks to the evidence of meat contamination with bacteria and other unhealthy material due to the field handling), and the take has dropped since.

Lyn is amongst those who say the government counts cannot be believed. For one thing they are not taking into account after-flood die offs which take out 100,000s. “They die off within two weeks; they don’t consider numbers killed on the roads; natural predation; drought or disease.” She agrees with the researchers who have taken apart the counting methodology itself.

Few people know that the amazing abundance reflected by official kangaroo numbers is a function of applying mathematical creativity to relatively small on-ground samples.

Visual samples are collected annually or tri-annually by national parks staff flying transects by fixed plane or helicopter across the countryside. A kangaroo count per zone is averaged for density, often based on clusters seen on the ground and some mysterious algorithms applied back in the office.

In NSW, that density figure is then multiplied by the total square kilometres in the related kangaroo ‘management’ zone, previously called harvest zone. The zones cover most of the state.

Multiplying in this way across a whole zone disregards the kilometres of pest-managed agricultural land and urban settlement that likely have nothing near the average density of kangaroo. Public land, as in parks and reserves, are notionally not sampled although it has been claimed in one research project that in the past the samplers have gone there as well, bumping up the raw numbers.

So-called ‘correction factors’ are used and increased in some areas where kangaroos have long been shot to estimate animal density the aerial spotters argue are just hidden from view, not absent.

It doesn’t take an advanced degree to look around. Like other observant Australian citizens and disappointed visitors, Tom and Lyn, who make it their business to observe what is happening to their regional kangaroo population, ask: “Where are all these millions of roos that the government claims to have counted?”

Tom has criss-crossed the region as a truck driver and Lyn also spends time on country roads. They both say they rarely see a kangaroo these days.

Says Tom: “We had a bloke come out with a machine on the bottom of a helicopter doing the grid for minerals. Flew all over the country. I said how many roos do you reckon you see flying all over like that? He said, I might count 10 a day if I’m lucky. They were flying millions of acres and they weren’t finding any. That country used to have tens of thousands of roos.”

Tom King, now 61, has been hunting kangaroos since he was 12 years old. Today he drives trucks for his main living. As a youngster he shot roos for pocket money around school hours, bagging five or six a day for skins. Later with motorbike, while working on the land, he shot kangaroos on a Friday afternoon and sold them in town. He says it bought him a café meal, movie and cigarettes so he could save his wages. As is commonly the case, it runs in the family. “Dad done it when he wasn’t fencing or droving. Dad always shot kangaroos to make more money.” Tom King’s son Tom Jnr also has worked as a roo shooter.

When he was selling lots of carcasses in the 1980s skins dominated the overseas market. That started drying up in the late 1980s.

That was when once-active conservation groups and zoologist Peter Rawlinson convinced the Americans and the odd celebrity to do without kangaroo leather – by showing that an Australian government public relations campaign, citing vast kangaroo numbers (but less than half being cited in 2017), was misleading. The Americans also pulled away because Australia did not have what US law required: a conservation plan for the species.

Australia still only has a commercial harvesting plan to this day, ie the yearly population counts and quotas published by the federal government based on those state aerial surveys. By the early 1990s the UK animal rights group VIVA was also starting to successfully lobby against the skin and meat trade on the other side of the Atlantic.

That the kangaroo trade long operated under allegations of organised crime profits and official corruption was unpacked by Raymond Hoser and Fairfax journalist Fia Cummings in books and newspaper reports up to 1996. Tom and Lyn told me everyone knew in the ‘80s and ‘90s of organised crime elements (with some recurring names) that, it was commonly, alleged led to more than one murder. Everyone on the bottom rung of field shooting, relying on making a few dollars as the sun rose and the carcasses were handed over, was cautious of talking about the industry heavyweights.

I ask Tom what the turning point was for him to start speaking out. He told a story that shows how myths grow and illustrates the renewed showdown between the wildlife and what people decide to produce – because they can on their private property.

He said it happened 7–8 years ago as everyone continued going into cattle and everyone was “hating sheep and hating kangaroos”. At the time a major local land owner started growing cotton around Cunnamulla. Kangaroos don’t eat cotton. “But they’ll eat every blade of green grass between the rows.

“So as soon as they started watering the cotton, kangaroos for miles started swarming in.” That family owns property all around Cunnamulla. “So then they said they had kangaroos in plague proportions, gotta do something. So they got a mitigation permit and wiped them out.”

Tom turned to trucking for a living. “I was carting cattle from Georgetown, Normanton right back to Charleville. Lot of good ‘roo country there. Some nights I wouldn’t even see a kangaroo (that was four years ago) would be less there now.”

By 2018 Tom King was telling anyone who would listen (and he says that did not include the authorities he tried to talk to) about what he’s seen and heard of conditions in Central Queensland during the recent five- to seven-year drought on top of the grazier stocking changes.

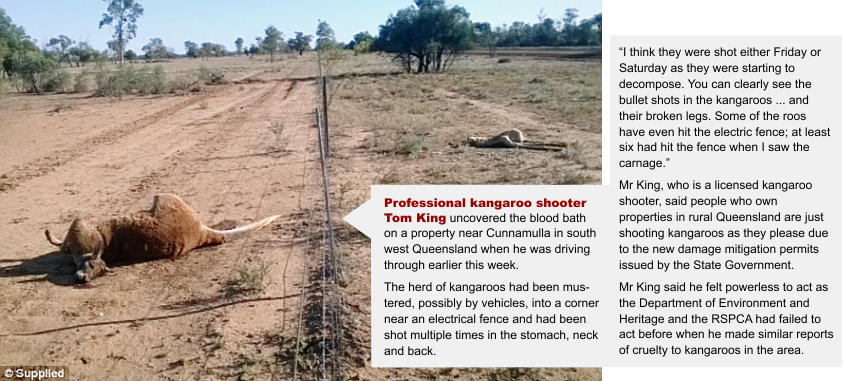

In 2015 he told the Australian Society for Kangaroos, which passed it on to the media, about a slaughter he came across where kangaroos had been herded against a fence, riddled with bullets and left to die. The Daily Mail reported it with photos:

The Labor state government has been on board to help the graziers. Lyn shows me a damage mitigation permit now issued in Qld. It’s for killing unlimited numbers of wallabies over three years. She notes there is no such thing as a re-location permit.

On one property, says Tom: “He’s got a mitigation permit, so invited shooters – ‘got a job to wipe them out whatever they are’. There were six cars in that convoy all had buggies on the back. Gun racks and cases on every one. They were there for three weeks. When the commercial roo shooter went out there, all he could find was roos laid out everywhere.” Lyn adds: “Professional shooters can now add 50 roos at a time for ‘recreational’ personal use. That all has to go.”

Tom believes fewer Red kangaroos are migrating to Central Queensland from further west to feed. “Weekend warriors [or the odd enterprising professional] go way out west shooting them out there,” he says. Technology has made this possible with new roads and four wheel drives able to carry much more fuel than earlier.

They agree that policing is hard to do in big, remote country. And almost no-one will talk. The code of rural conformity is strong, meaning often no-one wants to hear either.

But, insists Tom, the ammunition sold tells the story. Like when 27 part-time commercial shooters around Cunnamulla shot 4,700 kangaroos in a five week period. At the same time the local gun shop sold 25,000 rounds. “None of those were sold to us, not one professional roo shooter. That was all sold in big boxes of ammunition to the graziers for getting rid of kangaroos.

“A man goes out and buys 10,000 rounds for a 22-Magnum a month. Why? What’s he shooting? That’s a terrorist act as far as I’m concerned.”

Tom talks about a site he has seen on Facebook aimed at recreational shooters. It’s all about filling your car with big old dead kangaroos. A site that sells four wheel drives and guns. He cites another Facebook page for a regional firearms dealer that boasted of selling 30,000 rounds in four hours for mitigation work.

Bringing in the “weekend warriors” to have fun and destroy the wildlife theoretically still requires a mitigation permit. How accurate their shooting is a matter of dispute. The Sporting Shooters Association claims it is regulated to a professional standard.

However a quick check with police fact sheets on requirements for sporting shooters on rural properties and “game/vermin” control mentions nothing about shooting accuracy or professional standards. Permission is the big issue. On-ground evidence as shown in the Daily Mail report raises questions.

Tom and Lyn are also disgusted that no authority checks anything either before or after permits are handed out. Says Tom: “no-one goes out and counts the kangaroos to see if he’s got a roo problem; no-one goes out to check if the joey’s killed humanely, no-one does it.” Lyn claims that the government attitude since 2014 has been that while a drought is on, its job is to expedite issuing mitigation permits without inspections required.

They agree the whole scene looks a lot like genocide.

A recent ABC news story on relief for the gathering drought in NSW, quotes the state National Party leader, Deputy Premier, and representative for Monaro, John Barilaro, promising that NSW will take a leaf out of Queensland’s book and blame kangaroos for the drought conditions.

Making macropod killing easier will be part of the official response, he promised. Either the reporter or the National Party claimed the (let’s be polite and just say) ‘unlikely’ scenario that kangaroo populations “have soared … as a result of the drought”.

In parallel with the upswing in freelance mitigation shooting there is the cluster fencing that stops wildlife migrating to water and food or bails it up for the shooters.

Cluster fencing between adjacent landholders has been going up for the past five years in south-east central Queensland extending into northern NSW. Seventy percent of a reported $31 million cost for the fencing by the start of 2018 was paid for by the taxpayer. The fences are ostensibly to ward off dingos. (These fences stretch across the landscape joining and enclosing multiple properties which also still have their internal fencing intact.)

But says Tom the fences are “killing roos everywhere; they can’t migrate to water, can’t get to rivers because they are also fenced off. They estimate cluster fencing criss-crosses some 70 miles from Cunnamulla to the NSW border covering millions of hectares.

A 2017 media report about the Labor Premier of Queensland visiting the cluster fencing outside Longreach (and saying this was money well spent to save the sheep industry), cited cluster fencing then encompassing 300 rural properties and 4.3 million hectares, at a cost to the taxpayer of $27 million, the rest of the cost being picked up by producers.

A Kondinin sheep industry report promoting exclusion fencing went further stating that as of early 2016 “it is not uncommon” for fences to stretch to 200 or 300km in length enclosing 100,000 hectares.

Lyn notes there are laws against fencing all the way down to the water yet this is what’s happened. And public stock routes are being fenced. “In Paroo Shire you go to the Lands Department and they’ll say they’re all open stock routes; but now they’re full of stock, the gates are locked and the cockies got a big cluster fence going across.”

wildlife think they can go through

and they can’t get back out

or get water or food

“They have all these little corridors going in where kangaroos think they can go through and they can’t get back out or get water or food. There’s nothing – they die. It’s happening all around, Charleville, Mitchell, Morgan, St George … it’s happening everywhere. Emus, echidna; every wildlife … is caught in the fencing,” says Tom.

We discuss the government subsidy side of grazing in this unpredictable, boom and bust environment. It was raining along the coastal fringe when I talk with them, but not inland. Central Queensland is in its sixth or seventh year of drought. No-one has any money, says Tom. So on top of the regular drought and flood subsidies, the taxpayer is stumping up for most of the millions now going towards cluster fencing, for which even village businesses are applying.

Changing stock to cattle and heavy-grazing Dorper sheep worsened the on-ground effects of the drought. Many of the stocking changes were opportunistic as cattle prices rose and wool prices dropped (now reversing). Some involved absentee landholders who were moving cattle in and out. They weren’t neighbours in the traditional sense I was told by the long-time sheep grazier.

But the hard environment is not easy cattle country and everywhere stocking rates are paramount. Research suggests that competition with the macropods for grass emerges with overstocking. Drought on top is fatal.

The severe land degradation brought on by such landholder decisions is seldom appreciated by passing motorist who may see what appears to be a lot of kangaroos and wallabies eating road-side grass – often the only viable grass in the region. There are likely no animals on the other side of the fence.

Tom King has not made himself any more popular with his local critics by telling media people – that in his opinion – stocking decisions and treatment are in some cases as ignorant as the treatment of the wildlife; and that modern technology has put theory ahead of understanding. He’ll say things like:

“Fellow told me one day you gotta keep up with technology. I told him take that phone out of your pocket and tell that old ewe with her tongue hanging out there, she’s gotta walk another three kilometres to the yard.”

Or he’ll tell you about the fellow who caused stock deaths by turning off watering points that cattle had become used to over a period of 18 months while opening others. And then blame the wildlife. “Sheep and cattle haven’t changed. They can’t read a computer, and a kangaroo can’t read a computer either…”

Everyone blaming kangaroos for everything

“Yet,” says Tom, “everyone is blaming the kangaroo for everything (even) for the drought, and nothing is true… This day and age everyone hates kangaroos out in the western area, they hate ‘em. So some people when they have no stock, they turn all their waters off. There’s no kangaroo on that country now.” Or emus.

As an aside, the closure of man-made watering points has also become an article of faith with some strict parks managers, striving for an idealised return to an era considered more natural.

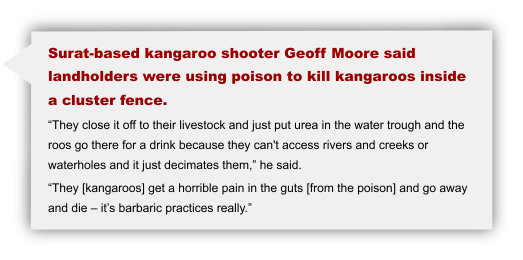

Poisoning of water sources is being reported in this renewed war on wildlife. According to a 2017 report by the national broadcaster, the ABC:

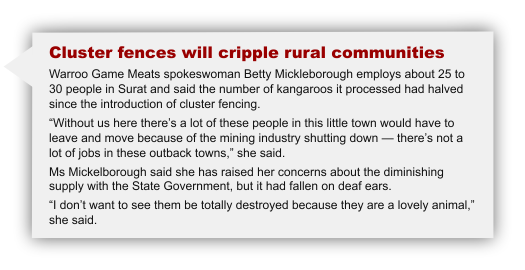

The same 2017 article (by journalist Elly Bradfield) checked with a regional kangaroo processing plant on whether the ‘harvested’ numbers were down in areas with cluster fencing and was told:

The clash between the kangaroo industry and the grazing industry in central Queensland, which either way results in dead kangaroos, has been bemoaned as poor government policy by the kangaroo industry and highlights the central dilemma of the Australian status quo: is the national icon a pest or a product (or something else entirely)?

Out of self-interest, the kangaroo industry is now the spokesperson for wildlife protection in this environment. The president of The Kangaroo Industry Association of Australia, Ray Borda, has criticised the lack of a holistic policy approach to land management in Queensland, saying measures as simple as protecting some wildlife corridors have been ignored.

The same article, looking at all sides, quoted at length from a grazing industry (AgForce) spokesperson saying graziers rely on government counts that purport to show that despite drought and destruction there are more kangaroos than at any time since 1992; that they feel confident with the claim by recreational shooters from the Sporting Shooters Association of Australia’s Farmer Assist program that they adhere to professional shooting standards and that the aim is to rebuild the sheep industry in the area.

Nikki Sutterby for the Australian Society for Kangaroos gave the same reporter a different perspective:

“The kangaroos were here first, so why can’t you give up ten percent of your land for your native animals? The research shows that when you graze kangaroos with stock it can actually increase production.

“The kangaroos are struggling too, but no one has any sympathy for them, everyone just wants them out of their property.

“But we know that when the rains come, they’ll head back out west and won’t be in everybody’s way, so why can’t we feed them just like we do with other livestock and animals? Just chuck them some hay, chuck them a bit of horse feed.

“Especially if it’s a tourist destination and you have tourists and travellers going through, I imagine they’d love seeing the kangaroos.

Kangaroos grazing Cunnamulla Cemetery. Townsfolk there testify that the kangaroos are coming in, hungry because of the lack of feed in the paddocks or at times to escape the shooting. Such scenes are not uncommon in rural communities throughout Australia. Australia’s premier animal protection organisation, The RSPCA, in Queensland (and elsewhere) contends wildlife and its treatment is not its problem or remit. Photo ABC News Elly Bradfield.

Lyn Gynther had a parting thought to city-dwellers who may still sometimes see hemmed-in kangaroos in urban spaces: “These people need to remember that all these cities that now take up so much space, (or for that matter grazing/cropping areas) used to be the ten-square-kilometre home-range of these animals. So they’ve just been pushed and pushed.”

IN THE 1999 edition of The Kangaroo Betrayed animal genetics specialist and veterinarian Ian Gunn from Monash Medical Centre foreshadowed what was likely to happen with practices that have been employed for 40 plus years in all states and, as we see in this western Queensland account, are being escalated to colonial pest removal proportions.

He wrote that continued culling and related practices involving rural production has the potential to precipitate the possible extinction of a number of species. Why?

“The evidence is indisputable,” he wrote. ”If left to continue [it] has potential to result in reduced genetic variability, lower reproductive efficiency and a radical reduction in population density below sustainable levels in certain regions of the country when associated with … seasonal conditions such as drought.”

Gunn wrote this sobering prediction some 20 years ago with pessimism about what modern civilisation has achieved in maintaining natural systems. “Civilisation seems hell-bent on a course of self-destruction; destruction of our environment, resources, wildlife and humanity itself.” (The Kangaroo Betrayed, 1999, p39. Australian Wildlife Protection Council Inc.)

It would not be fair to end this chapter putting all the blame on acts of humans. ‘Acts of God’ also play a role in the plight of the kangaroo species and governments’ inability to reliably predict populations. By ‘acts of God’ I refer to the weather and the recurrent and persistent drought phases that arguably come more frequently as a result of climate change (back to humans there).

In a recent conversation with a CSIRO scientist who also owns a grazing property in western NSW, this became manifest. This man is well disposed toward the remaining wildlife on his property. He’d even like to reintroduce some, like emus, but is up against a blank wall of negative bureaucracy on that count. (Re-introducing native predators, like the dingo, is a step even less open to discussion in Australia.)

He has destocked his land in the extended dry weather. But what happens on his block is also reliant on what is happening next door: the self-determined patchwork of neighbouring private property management. Affecting wildlife movement is how appropriately landholders stock sheep and cattle to suit conditions and whether they shoot kangaroos, wallabies, emus – or don’t. Having no national conservation policy for macropods means there is no regional approach or cooperation between neighbouring properties other than pest management or commercial kill.

The upshot is that some people have a lot of kangaroos on their land because there is feed for a while, because there is safety. In his case the haven extends to a neighbouring national park, not the best habitat and beset by drought as well. He has in recent times been faced with starvation of kangaroos, worsened by tick infestations, on a regular basis.

It is distressing to see. He has to undertake mercy killings. He says the number of Eastern Grey Kangaroos on his property in competition with other kangaroo species and wallabies for the little remaining forage under drought conditions is not sustainable. Further exclusion measures need to be taken. Maybe fence-off water sources.

Government counts and comfortable kill quotas do not reflect this sombre scenario under climate challenges for Australia’s most iconic animal.